Elegy, an individual response to the death of a person or a group, began in Greece and Rome as a particular metrical form. But elegies are among the greatest poems in every language, whatever their form. Traditionally, they mirror three elements of mourning: grief; memories of the dead; and some kind of consolation – because people in grief often find relief in poems expressing a loss they thought was unique to them.

But elegy took me completely by surprise, just as death itself can do. When I began work on my new collection Emerald, I was simply interested in the gems themselves, their mining, myths, geology, history. I talked to emerald cutters, pondered the paradoxical symbolism of green, colour of envy and poison as well as magic. Then, very suddenly, my 97-year old mum was rushed to hospital. During that dark time, the emeralds surprised me by triggering a flood of poems about her: her jokes and determination, the pleasure she took in talking to old friends, the generous mutual support of everyone in the family as she died; my childhood memories of her; snapshots of her childhood.

After she died, I realised that because she was a biologist, and passionate naturalist, these jewels signifying spring, hope and renewal were also offering, totally unexpectedly, true elegiac consolation in the saving green of nature.

Elegies are a rich seam in poetry, so I have divided my choices into 10 distinct sub-genres.

1. Elegy for a child: A Part Song by Denise Riley (from Say Something Back)

The worst loss of all. Riley’s heart-rending poem on the death of her adult son follows a powerful tradition of lament for children that includes the 14th-century poem Pearl, in which a father loses his “pearl” in a garden, and Ben Jonson’s poem On My First Son. Riley’s poem begins by questioning the point of poetry and “song”, but goes on, through vivid domestic memories evoking the infant, the boy and the man, to demonstrate how very powerful elegy can be, and how loss is at the heart of all lyric poetry.

2. Elegy for a mother: Freud’s Beautiful Things by Emily Berry (from Stranger Baby)

Nearly everyone loses a mother. But relationships with mothers vary and everyone’s loss is different. Seamus Heaney’s sequence for his mother, Clearances, is gentle and measured; Berry opens her breathtaking book on her mum’s death (when she herself was seven) with Freud’s comment that “the loss of a mother must be something very strange”. Freud’s Beautiful Things is an exquisitely controlled journey through loss, chaos, hurt and anger, but also love and hope.

3. Elegy for a father: Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night by Dylan Thomas

Thomas’s poem for his dying father is a villanelle, a form in which two lines repeat (just as thoughts recur obsessively in grief) and appear together in the hard-hitting ending: “Do not go gentle into that good night. / Rage, rage against the dying of the light.” Sylvia Plath’s poem Daddy is a more savagely conflicted variation, driven not only by loss but by the fury at abandonment that also needs to be acknowledged in mourning. “I was ten when they buried you. / At twenty I tried to die / And get back, back, back to you.”

4. Elegy for a wife: Orpheus and Eurydice by Czeslaw Milosz, translated by the author and Robert Hass (from Selected and Last Poems, 1931-2004)

In this marvellous poem, the Polish-Lithuanian Milosz, entering the hospital to visit his dying wife, becomes Orpheus braving the underworld and failing to recover Eurydice. Another more recent, devastating elegy for a wife is Ian Patterson’s The Plenty of Nothing, for Jenny Diski. Further back in this tradition are Milton’s sonnet, Methought I saw my late espoused saint, and Thomas Hardy’s The Voice, the latter written at a moment when the death of his wife, with whom relations had broken down, turned a great novelist into an even greater poet.

5. Elegy for a husband: Elegy for my husband by Toi Derricotte

This harrowing poem foregrounds injustice in her husband’s early life: “the aunt bleeding out on the highway / (too black for the white ambulance to pick up).” It memorialises his body: both her own memories of it (“the hand that laid itself over my heart and saved me / the eyes that held the long gold tunnel I believed in”) and its private past: “muscles which white girls longed to touch / but must not … You would be lynched in that all-white town you grew up in.” The poem ends with bare, inescapable loss: “All that is gone.” The only consolation here is in the artistry, the true placing of beautiful, powerful words.

6. Elegy for a brother: Poem 101 by Catullus, translated by Anne Carson

(from Nox by Anne Carson)

This famous Latin poem was written in original “elegiac couplets” by the Roman poet Catullus for his brother, who died far away from Rome. Tragically aware it is addressing “silent ash”, the poem ends ave atque vale, “hail and farewell”. Carson memorialised her own dead brother by translating this as the centrepiece in a memory-box of scraps for her brother: a box that Carson (echoing Catullus’s Poem Five which says, “once our brief light is set, we must sleep a perpetual night”) labelled Nox – “Night”. An echo-box that doubles as a tomb.

7. Elegy for an idealised girl: She Dwelt Among the Untrodden Ways by William Wordsworth

A lost loved girl is a potent muse. Wordsworth’s “Lucy” poems evoke unrequited love. Scholars argue whether she really existed, this Lucy who lived and died unnoticed by everyone but Wordsworth, who never told. His haunting poem projects onto Lucy his own sense of loneliness and loss, just as it was the death of a friend’s daughter that inspired Bohemian-Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke to write his mysterious elegiac sequence Sonnets to Orpheus, in which the archetypal poet searches for the dead girl he will always fail to bring back to the light.

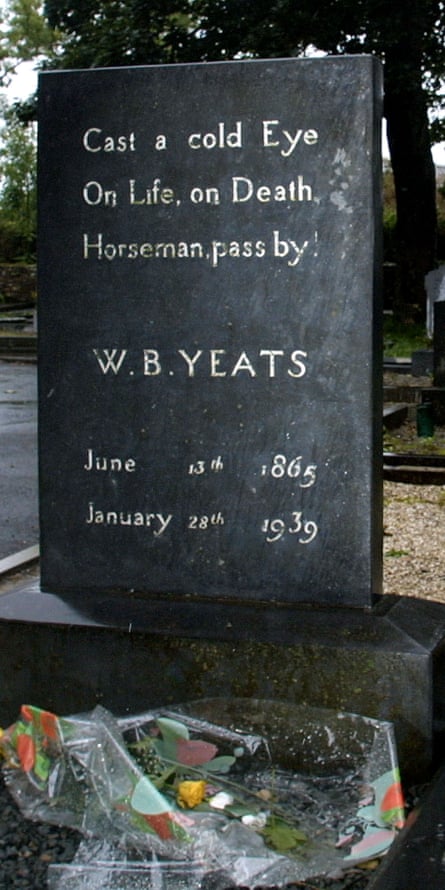

8. Elegy for a fellow poet: In Memory of WB Yeats by WH Auden

A poet’s sense of vocation can be tipped into crisis by the death of another poet whose work they passionately admire. Thomas Gray’s Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard was probably inspired by the death of poet Richard West; Shelley’s 55-stanza poem Adonais is an elegy for Keats. And Auden’s elegy for Yeats is a touchstone for all poets, reminding us that poetry, the generative lens through which poets see the world, “makes nothing happen”. But also that poetry “survives / in the valley of its making”.

9. Elegy for a friend: In Memoriam by Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Poets are often close friends, so categories eight and nine overlap. One recent elegy I find especially poignant is Don Paterson’s poem Two Trees for his dear friend, poet Michael Donaghy. The great English prototype of elegy for a friend is Milton’s poem Lycidas: published, like Shelley’s Adonais, the same year the friend drowned. Tennyson, though, took 16 years to finish his 133 cantos. In Memoriam is a goldmine of deep-felt grief, summing up the centrality of loss to human life: “Better to have loved and lost / Than never to have loved at all.”

10. Elegy for a group: Requiem by Anna Akhmatova translated by Judith Hemschemeyer (from Complete Poems of Anna Akhmatova)

Elegies for a group are among the most profound poems of all. Death Fugue by German-speaking, Romanian-born Paul Celan is one of his most famous poems but all his work memorialises victims of the Holocaust; as Michael Longley’s Wounds elegises victims of the Northern Irish Troubles and Thom Gunn’s collection The Man with Night Sweats addresses Aids-related deaths in the 1980s. Akhmatova’s Requiem memorialises the suffering of the Soviet Union under Stalin’s purges. Refusing to go into exile, she dangerously carried it with her, writing and redrafting it for three decades, in towns across the Soviet Union. “The ones who smiled / Were the dead, glad to be at rest.”

- Emerald is published by Chatto & Windus, priced £10. It is available from the Guardian bookshop for £8.50.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion