On the second floor of an unassuming office building in Shibuya, Tokyo, a process of transformation is happening.

“We don’t want to stand out,” says Hiroko Minamoto, president and co-founder of video game translation firm 8-4. The company, named after the final level of Super Mario Bros, specialises in repackaging Japanese video games for English-speaking audiences, or vice versa. “When localisation is bad, that’s when it stands out, and that’s when people yell at us. We want it to be natural.”

John Ricciardi, executive director and co-founder of 8-4, adds that it is satisfying when people feel the firm has contributed so much to a game that they talk about it. “It’s always nice when that happens.”

Game localisation is a process that involves not only language translation, but also checking such elements as accuracy, consistency, quality and cultural differences, as well as suggestions to developers for improvements. In practice, it involves spreadsheets and emails – lots of them – and can infuse a game’s writing with energy and personality, or leave it flat and lifeless.

“We always noticed cultural and language gaps between Japan and other countries,” says Minamoto, “and because of that, a lot of good things weren’t able to happen. The philosophy of 8-4 is to try and get rid of that gap.”

The workload varies considerably from project to project, depending on the amount of text and voice work involved. Big role-playing games (RPG) such as Xenoblade Chronicles X are story-heavy and can take, on average, 60-70 hours to finish, as they contain huge amounts of text. Ricciardi estimates such games can be year-long projects, with up to 10 people working on them. Then there are smaller projects, such as mobile and indie games, some of which only take a week or two.

Voice dubbing in high-budget games is another process that can take staff away from the office for months. “To do English-language dubbing well, you have to do it in California – the other side of the world,” says Ricciardi.

8-4’s role in overseeing voice dubbing is as essential as that of a director. While a director is focused on coaxing the best performances out of their cast, they can’t be expected to know every last thing about the game and its characters. That task falls to the developer or, in the case of dubbing, the localiser.

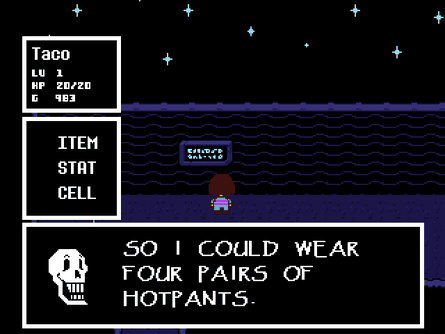

In the English-speaking world, a lot of attention is paid to the localisation of Japanese games. But 8-4 does the reverse as well: helping games created in English get in front of Japanese audiences. The firm’s latest project is the quirky RPG Undertale, which is filled with esoteric humour and is therefore a huge translation challenge.

One hard to translate gag involves the characters Papyrus and Sans, two skeletal brothers who speak in their respective typefaces in English (the spindly Papyrus font and the much-maligned Comic Sans). In 8-4’s version, Papyrus speaks in a faux hand-drawn vertical script, while Sans speaks in a cutesy irreverent typeface one might find on an advert or television variety show.

“A lot of indie developers grew up playing Japanese games: that’s where they got their inspiration and what made them happy as a kid,” says Ricciardi. “We often hear, ‘I realise these games might not sell that well in Japan but I just want to give back’, or ‘I want to see my game out in the place that was magical to me as a kid growing up’.”

Minamoto laughs. “They are passion projects for us as well,” she says.

The quality of English to Japanese translations frustrates the 8-4 team. “I’d compare it to what it was in the west in the 80s or early 90s,” says Ricciardi. “There are a lot of ugly fonts and weird decisions because there is not a lot of education and it is a hard thing to do. Some games are just machine translated, which is really bad.”

Minamoto adds: “If a game gets care, if we show it love, then Japanese audiences really appreciate it. Even things like fixing line breaks and using the right font make a difference.”

Another 8-4 project, Nier: Automata, received widespread praise last year as a game with a dense, multilayered narrative and powerful emotional resonance, much of it thanks to the detailed translation. “We asked [Nier: Automata director Yoko Taro] a lot of questions,” says Ricciardi. “We try and get as much information as the developers are willing to give us.”

The team has previously localised three of Taro’s games into English, so they have grown used to each other’s working style.

“Yoko-san knows that we are going to have a lot of questions and we want to know everything before we translate stuff. He appreciates it,” says Minamoto.

“He either loves it or hates it,” says Ricciardi, “but either way, he keeps coming back.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion