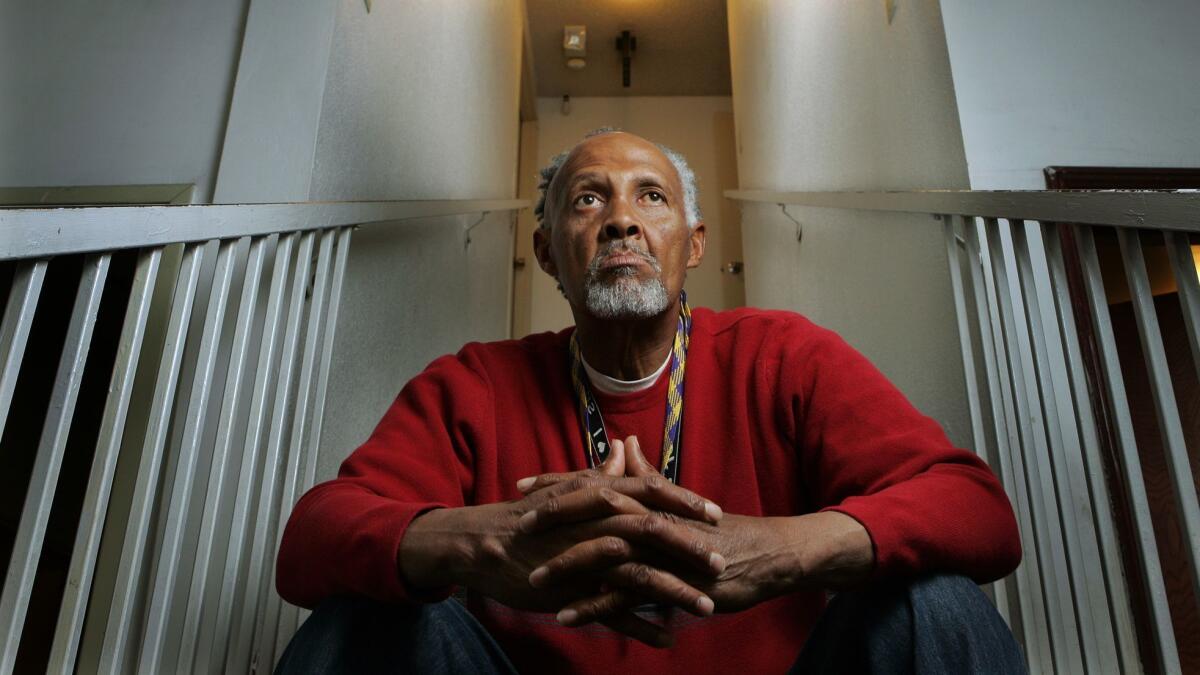

Locals mourn former San Diego hoops star Oscar Foster

Oscar Foster, a former basketball standout for San Diego High, San Diego City College and the University of San Diego described as “one of the local legends” by basketball Hall of Famer Bill Walton, died last month. He was 69.

A kind person and outstanding student as recalled by Jerry Eucce, a former prep and collegiate teammate, Foster was 6-foot-7 yet graceful, Eucce said, when he joined the San Diego High varsity as a sophomore in 1965.

First time they met, Eucce said, he threw him a basketball and Foster snagged it with one hand.

Foster would draw recruiting overtures from more than 185 colleges, while becoming the top career scorer in the San Diego Section and also helping the Cavers win a pair of section titles.

“Here was a guy who was such a spectacular player and could do anything on the court with or without the ball,” said Walton, a San Diegan who saw Foster and other standouts in games at Municipal Gym at Balboa Park. Eucce said his former teammate was “phenomenal” at basketball.

However, although Foster would lead USD in scoring as a senior and join a pro exhibition team, an NBA career was not part of his future.

In the 1970s, he showed signs of mental illness. He would be diagnosed with schizophrenia, which the National Institute of Mental Health describes as chronic and severe mental disorder that affects how a person thinks, feels, and behaves. Symptoms usually start between ages 16 and 30.

The former teammate Eucce became a San Diego police officer. While patrolling downtown in the 1970s, he saw Foster talking to lamp posts. He was responding to voices in his head.

Eucce bought Foster shoes and lunch and made sure he had lodging at a county facility. This happened a few times.

“He’d still always remember who I was. And he’d always say hi Jerry, and we’d always have a great conversation,” Eucce said.

Mental illness wasn’t in Foster’s family history, per a records search for a U-T article in 2007.

“For that to happen to him, it just shows you mental illness can happen to anybody,” Eucce said.

Foster was the San Diego Section Player of the Year in 1967 before accepting a scholarship offer at Minnesota, a choice he later regretted. Though he scored 18 points per game and earned all-Big Ten Conference honors playing on the freshman team (freshmen were ineligible then to play varsity), he got homesick and returned.

When Foster reunited with Eucce on the City team, in 1969, Eucce noticed no concerning changes in his former teammate’s personality.

“Same as he was in ’65 — a big, gentle, giant,” Eucce said. “He was the calmest, mildest, nicest person in the world.”

Foster, the squad’s leading scorer at 20.4 points per game, simplified basketball for his City teammates. “He told me: ‘Just bring the ball to half court and throw it to me, that’s all you need to do,’ ’’ Eucce said.

In two seasons at USD, the forward played in 50 games under Bernie Bickerstaff, a future NBA head coach. As a senior, he made 80 percent of his free throws and 51 percent of his floor shots and averaged 16.5 points and 7.9 rebounds per game. Bickerstaff noticed changes in behavior, though. He noticed less drive.

About then, Foster married his teenage sweetheart, Jane Martin. Their union produced a son, Oscar Beau Foster. The marriage didn’t survive unexpected changes in Foster’s behavior, Beau Foster told the U-T in 2007.

Eucce chatted with Foster as recently as 2008. About then, he took Foster to an event that honored him as San Diego High’s top athlete of the 1960s. “He couldn’t say much, but he said thank you,” Eucce said.

Oscar Foster, in comments to the U-T in 2007, said he “really wasn’t the greatest athlete” in high school. “I want you to get these names down,” he said. Foster named Helix High’s Walton, San Diego’s Richard Mills, Crawford’s Von Jacobsen, Morse’s Monroe Nash and San Diego’s Art “Hambone” Williams as players from his era he considered better than himself.

Walton, though, called Foster “the icon” of the era.

“Off the court,” Walton said, “he was so friendly and so gregarious, so willing to help anybody and everybody.”

Foster’s survivors include his brother, Wilbur Foster Jr., his son, his daughter-in-law, Jenn, and two grandchildren. The family requests that donations go to the San Diego Rescue Mission (https://www.sdrescue.org/), a non-profit, faith-based organization that assists the homeless.

A memorial service is scheduled for noon Friday at Salli Lynn Chapel at Greenwood, 4300 Imperial Avenue, San Diego.

Tom.Krasovic@SDUnionTribune.com; Twitter: SDUTKrasovic

Go deeper inside the Padres

Get our free Padres Daily newsletter, free to your inbox every day of the season.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.