For a decade, some security professionals have held out extended validation certificates as an innovation in website authentication because they require the person applying for the credential to undergo legal vetting. That's a step up from less stringent domain validation that requires applicants to merely demonstrate control over the site's Internet name. Now, a researcher has shown how EV certificates can be used to trick people into trusting scam sites, particularly when targets are using Apple's Safari browser.

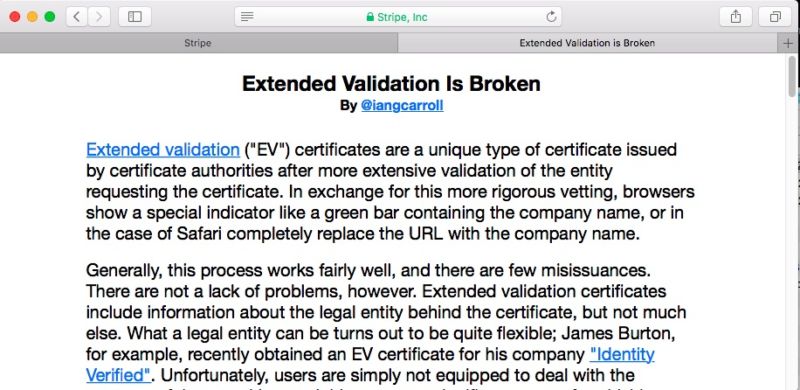

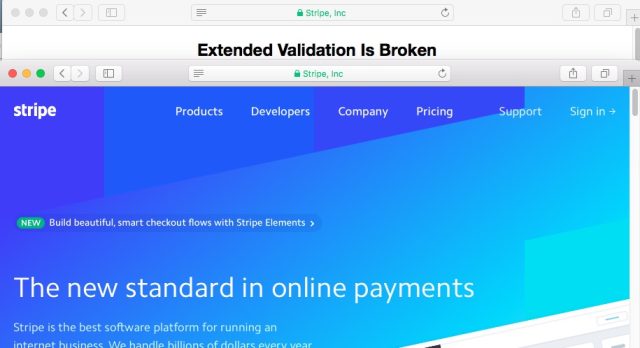

Researcher Ian Carroll filed the necessary paperwork to incorporate a business called Stripe Inc. He then used the legal entity to apply for an EV certificate to authenticate the Web page https://stripe.ian.sh/. When viewed in the address bar, the page looks eerily similar to https://stripe.com/, the online payments service that also authenticates itself using an EV certificate issued to Stripe Inc.

The demonstration is concerning because many security professionals counsel end users to look for EV certificates when trying to tell if a site such as https://www.paypal.com is an authentic Web property rather than a fly-by-night look-alike page that's out to steal passwords. But as Carroll's page shows, EV certs can also be used to trick end users into thinking a page has connections to a trusted service or business when in fact no such connection exists. The false impression can be especially convincing when end users use Apple's Safari browser because it often strips out the domain name in the address bar, leaving only the name of the legal entity that obtained the EV certificate.

"With enough mouse clicks, you may be able to open a system certificate viewer or get your browser to show you the city and state," Carroll wrote. "But neither of these are helpful to a typical user, and they will likely just blindly trust the bright green indicator."

Carroll's demonstration comes three months after researcher James Burton exposed a different way EV certificates can be used to trick end users. He established a business named "Identity Verified" and showed how the resulting EV certificate might be used to add the air of authenticity to a scam site. Both Carroll and Burton said little effort was necessary to create the legal entities. Carroll said the demo cost $177: $100 in incorporation expenses and $77 for the certificate.

The demonstrations are generating productive discussions among developers about the way EV certificates should be treated in browser user interfaces. Security professionals are also openly discussing whether certificate rules should be modified to prevent these types of cases.

For the time being, people should remember that EV certificates aren't automatically a panacea for online fraud. In some cases, certificates could make an otherwise obvious scam site seem legitimate. When in doubt, end users should carefully inspect the certificate and ensure it was issued to the operator of the trusted site.

Listing image by Insight Pest / Flickr

reader comments

92