Chronic intestinal disturbances may in part be handed down from above, according to a study published Thursday in Science.

Intestinal pathogens can lurk in the mouth and—at just the right moments—interlope in the gut to help trigger severe, recurring bouts of inflammation, researchers found. The study, based on human and mouse data, suggests that microbes lying low around our choppers may play a role in persistent gastrointestinal conditions such as Crohn’s Disease and ulcerative colitis.

“Our findings suggest that the oral cavity may serve as a reservoir for potential intestinal pathobionts that can exacerbate intestinal disease,” the researchers, led by Koji Atarashi of Keio University School of Medicine, concluded.

Atarashi and colleagues wound up researching mouth microbes after noticing that the fecal microbiome samples of patients with chronic gut troubles tended to have far more oral bacteria than healthy people’s samples. They hypothesized that the oral germs—guzzled in the roughly 1.5 liters of saliva we swallow each day—may intermittently move through the gut and provoke aberrant immune responses and inflammation.

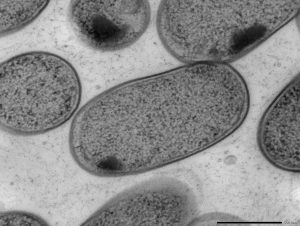

To test out the theory, the researchers had germ-free mice take in saliva from two patients with Crohn’s disease. Saliva from one patient had no effect on the mice. But saliva from the other did—it caused a raging immune response in the rodents' intestines. The researchers sifted through the bacteria in that saliva sample and found that a drug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strain—2H7 (Kp-2H7)—was behind the immune mayhem.

Intestinal interlopers

To shore up the results, the researchers repeated the experiment from the beginning. They took more saliva samples, this time from patients with ulcerative colitis, and again gave them to germ-free mice. And they again saw inflammation from some saliva samples and pinned it down to a Klebsiella strain. This time it was Klebsiella aeromobilis 11E12 (Ka-11E12).

Going back to the fecal microbiome samples that started it all, the researchers looked specifically for Klebsiella strains. They found that patients with inflammatory bowel diseases had significantly higher aggregated relative abundance of Klebsiella strains in their poop than that of healthy people.

In an accompanying editorial, immunologist Xuetao Cao of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences concluded:

These data strongly indicate the pathogenic role of oral cavity-derived Klebsiella strains in inflammatory diseases, although so far the data are correlative.

The data needs far more work to repeat, verify, and extend the significance of the findings to patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. That said, Cao notes that this preliminary data hints that oral treatments to eject Klebsiella strains from the oral microbiome may have a future in helping to treat such conditions.

Science, 2017. DOI: 10.1126/science.aan4526 (About DOIs).

reader comments

93