Tempus fugit. Tomorrow, Adrian Mole is 50. We can be precise about this. In the book that introduced him to the world, The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole Aged 13 ¾, Sue Townsend’s famous diarist noted in his entry for 2 April 1981, “I am fourteen today! Got a track suit and a football from my father. (He is completely insensitive to my needs.)” When this first volume of his diaries was published in 1982 we found him nursing his unappreciated intellectual ambitions – “I saw Malcolm Muggeridge on the television last night, and I understood nearly every word” – and, above all, looking forward to growing older. His diary entry for his birthday ends with him looking in the mirror. “I think I can detect a certain maturity. (Apart from the rotten spots.)”

Well, grow older he did, the spots giving way to even worse afflictions. Over the next quarter century, Townsend charted the tragic-comic vicissitudes of his life in seven further volumes of his diaries. In these he lived through the same times as the rest of us and grew older at just the same rate. The final volume of his observations and anecdotes, Adrian Mole: The Prostrate Years, appeared in 2009. It found the Pepys of modern Leicestershire approaching his 40th birthday, which duly takes place, in appalled capital letters, near the end of the book. Time moves on, but disappointment is pretty much a constant. “My presents were the usual rubbish, apart from a Smythson A4 moleskin notebook, which came in the post from Pandora.” Petrarch and Laura; Heathcliff and Cathy; Adrian and Pandora: the great literary love affairs are unconsummated, and Pandora Braithwaite remains the impossible object of Adrian’s love and desire. In this last volume, Adrian actually gets to spend the night in the same bed as her – though, of course, nothing happens except sleep.

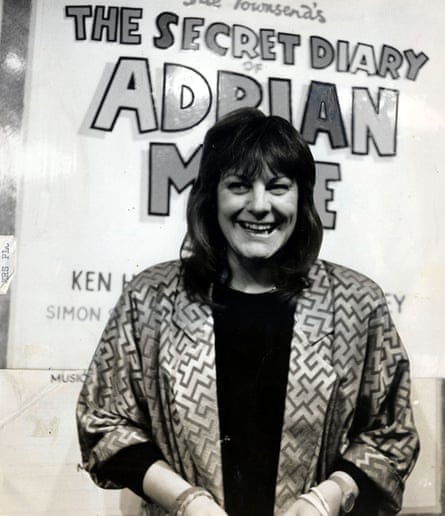

Would Adrian and Pandora have ever become lovers? In The Prostrate Years, Adrian’s wife, Daisy, has left him for a wealthy if dim-witted local toff, so our hero is once again available. At the very end of the book, as Pandora’s Audi draws up outside Adrian’s house and he walks towards her, we are free to speculate. For there would have been more. Townsend had plans for further Mole diaries and there is every indication that we would have been able to keep company with him deeper into his middle age if his creator had not died in 2014, at the age of only 68. According to her publisher, she was working on a new volume, provisionally entitled Pandora’s Box. Townsend was always going to return to Adrian Mole. His birthday was her birthday too, a clear enough clue that he was her indispensable alter ego as well as a figure of fun.

Ageing has become an irresistible narrative technique in popular culture. Harry Potter was 11 for the first volume of his adventures, felt more and more the darkening powers of adolescence over succeeding volumes, and departed from his readers in the seventh volume as he was about to turn 18. Bridget Jones, suspended at thirtysomething for Helen Fielding’s original newspaper column, duly matured and ruefully passed 50 for Bridget Jones: Mad About the Boy. (She was still in her early 40s for the film Bridget Jones’s Baby.) On both page and screen she looks back with us on her more youthful follies. Even the never-young Alan Partridge has been made to feel the passing of the years as he has progressed from radio to TV to film and now to life as a literary character. In his latest blithely incompetent and conceited memoir, Nomad, he confesses himself to be “pushing sixty” (but therefore presumably older). His body is not quite what it used to be. “I’m not ashamed to admit that since 2010 my buttocks have become increasingly slack and gelatinous.” So he embarks on a long-distance walk from Norwich to Dungeness, a trip his father once failed to make for a job interview at the power station – a “sepia-tinted journey of yesteryear”. Vaunting his new-found reflectiveness, he is still as unself-knowing as ever.

The French have a term – roman fleuve – for the novel sequence that takes a cast of characters through the years. There should be a matching name (le protagoniste vieillissant?) for the fictional character who grows older in real time, through succeeding volumes and different stages in an author’s own life. Such a protagonist is a special kind of companion. In the past it was common for fictional characters who reappeared in one book after another never to age. I remember noticing, aged nine or 10, that Biggles, dashing hero of my favourite tales of adventure, had flown for the RFC in the first world war (admittedly while still in his teens), been an air ace in the Battle of Britain, and then, in the 1950s and 60s, worked for Scotland Yard in their special air police division with his also still sprightly friends Algy, Ginger and Bertie. What elixir of youth had he drunk?

Townsend liked to recall that William Brown, Richmal Crompton’s buoyant yet fatalistic protagonist, was her prototype for Adrian. She had devoured the tales of his exploits when a child. William featured in some 40 books over half a century. Yet though his author took account of changing times (motor cars, the second world war, television) her antihero remained forever 11 years old, an unageing monitor of adult follies and vanities. That other great protagonist of the English comic novel, Bertie Wooster, remained similarly forever young. He was a gormless, emotionally susceptible chap in his 20s when he first blundered into life in 1917 and remained no older and absolutely no wiser through many a misadventure over the next five decades.

These characters live in some golden age, eternally youthful, brave and foolish. Their wise creators could never let them become sour. In contrast, Adrian Mole takes us through our own times and our own disillusionments. He lives through Thatcherism and Blairism and pronounces judgments on both with his usual self-serious sagacity. At the end he is writing letters to prime minister Gordon Brown about the complications of his tax affairs. In this respect he is just like those protagonists created by some of the great American novelists of the late 20th century. Three of the most stylish and sombre of these – John Updike’s Rabbit sequence, Philip Roth’s Zuckerman novels, and Richard Ford’s Frank Bascombe narratives – have pursued a fictional alter ego across the decades of their nation’s history. All three mark the events of their lives with reference to political events and great socio-economic movements.

Bascombe is first encountered in The Sportswriter (1986), in his late 30s, and is subsequently the narrator – perhaps the hero – of three further novels. In The Sportswriter he is a would-be novelist who makes his living writing about sport. A divorce and the death of his son behind him, he seems to be becoming detached from his own life. Independence Day came nine years later and found Frank nine years older and selling real estate. The Lay of the Land (2006) took him into his mid-50s and contemplating a second failing marriage as the votes for George W Bush and Al Gore are being recounted in Florida.

By the fourth volume, Let Me Be Frank with You, published in 2014, he is in his late 60s and is enduring retirement. He has aged at exactly the same rate that time has passed for his readers. His second marriage holds together, though one memorable episode is his visit to his ailing first wife in her luxury care home. The past stretches before him as it does before the novelist. The book’s very title seems to be Ford’s signal that he is helplessly attached to his ageing everyman. Yet Frank’s latest volume is really a collection of four separate novellas, as if the assurance of an overarching narrative were disappearing with age.

Across all those years, Frank is always switching into the present tense, trying to catch the ordinary and the actual as it happens. As he says at the end of The Lay of the Land, “Here is necessity. Here is the extra beat – to live, to live, to live it out.” The tense is appropriate, for the hero who has outgrown a single novel no longer lives inside a narrative with a decided shape. Updike settled on a continuous present tense for his Rabbit novels. These track the life of Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom from his mid-20s in Rabbit, Run (1960) – which Adrian Mole is diligently rereading in The Prostrate Years – to his mid-50s in Rabbit at Rest (1990). The present tense in which each novel is narrated has him trapped in his time, whatever it is.

Rabbit does think that he knows his times. In the third volume, Rabbit Is Rich, we hear about the middle-aged protagonist’s waning enthusiasm for sex with his wife thus: “Somewhere early in the Carter administration his interest, that had been pretty faithful, began to wobble and by now there is a real crisis of confidence”. The presidential allusion comes from the character’s consciousness, so entangled does he think his story is with that of America. By now he is in his mid-40s and chief sales rep of the Toyota dealership in his home town of Brewer, Pennsylvania and (thanks to the money inherited from his father-in-law) affluent. Updike knows how to offer the satisfaction of consistency amid change: Rabbit is still that lecherous slob with a poet’s sensibility. Ever alive to physical details, he will switch easily from thinking of sex with his son’s girlfriend to lyrical details about the sounds of rain on the different kinds of leaves outside his kitchen. And he is alive to the changed shapes of middle-aged bodies, especially his wife’s and his own – now that he is so expanded “he has become a person and a half”.

All of these fictional Americans could manage laments like Adrian Mole’s: “What have I done with my life? I have lost two wives, one house and one canal-side apartment, a head of hair and my health” – though it takes Townsend to see that the disappointment is funny. Indeed, it sometimes seems that Adrian’s narrative parodies the melancholy ageing of more literary protagonists. The subtitle of Townsend’s final Mole volume, “The Prostrate Years”, is taken from the mistake that many of Adrian’s acquaintances make when he tells them of the cancer with which he has been diagnosed. “Why do so many people mispronounce ‘prostate’? I am sick of correcting them.” The prostate theme is one sure marker of a character’s progress down the vale of the years. In The Lay of the Land Frank Bascombe has prostate cancer. There is a compensation, which is that his disease brings his 25-year-old daughter, Clarissa, back to him. She tells him how well he “deals with things”. “She only believes this because I have cancer and my wife left me both in the same year and I apparently haven’t gone crazy yet.”

The “perfidious” (Frank’s word) prostate exerts its power over Nathan Zuckerman too. Roth’s Exit Ghost (2007), narrated by his alter ego, begins, “I hadn’t been in New York in eleven years. Other than for surgery in Boston to remove a cancerous prostate, I’d hardly been off my rural mountain road in the Berkshires.” Roth outdoes even Mole in the surgical specifics of his treatments (“… a catheter inserted in the urethra to inject a gelatinous form of collagen where the neck of the bladder meets the urethra …”). This is the final Zuckerman novel, so our once-sensualist narrator, though gifted with every evocative word he needs, must be robbed of his inspiriting libido.

Zuckerman is 71, incontinent and impotent. In the hospital where he is being treated he sees a woman he once knew, Amy Bellette, first encountered 50 years earlier in The Ghost Writer (1979). He is reading the short stories of EI Lonoff, the masterful writer he visited in that earlier novel, and the dissolution of whose marriage he witnessed. The allusion reminds us that we are at the end of a long line of Zuckerman novels that has sometimes seemed to follow the path of Roth’s own career. Zuckerman has not exactly grown old with us; he has grown old faster than us. Now he seems to rely on the reader for memories of his past sensualism. In Exit Ghost he agrees a house swap with a young married couple, Billy and Jamie, both writers. He is immediately “transfixed” by Jamie, and readers of earlier Zuckerman novels will recognise his fierce interest in his own sexual feelings. He is “subjugated as quickly as I imagined Billy to have been, though for reasons having to do with finding myself at the other edges of experience from him, at the rim that borders oblivion”. She makes him conscious of “the ghost of my desire”.

British novelists have occasionally attempted in all seriousness to take a single, changing yet consistent character through changing times across succeeding volumes. AS Byatt has done it in her four novels tracing the fortunes of Frederica Potter, a schoolgirl in the 1950s at the beginning of The Virgin in the Garden (1978) and, by the fourth volume, A Whistling Woman (2002), set at the end of the 1960s, an experimental writer and TV personality. Yet it is notable that each of these novels looks back from the time of its publication to some earlier era, its interest essentially historical.

A very different English – you might say, quintessentially English – example is Edward St Aubyn’s Patrick Melrose quintet. In the first volume, Some Hope, St Aubyn’s protagonist is a five-year-old child, first bullied by his frightening, sarcastic father, David – then raped by him. By the second volume, Bad News, Patrick is a drug addict in his 20s and his father is dead, though in memory and anecdote he will keep returning. Subsequent volumes take him into marriage and fatherhood. Finally, in At Last, he has a failed marriage behind him but, in middle age, the prospect of a relationship with his children unpoisoned by his own childhood. The spine of St Aubyn’s sequence is autobiographical; the times through which Patrick lives are a blur. There is none of that American sense of a character’s experiences expressing those of a nation or society.

It was probably an English novelist who first developed this way of using fiction to track changing times: in his six so-called Palliser novels, beginning with Can You Forgive Her in 1865 and ending with The Duke’s Children in 1880, Anthony Trollope wove stories involving Britain’s political classes centred on the character of Plantagenet Palliser. Notably this allowed him to deal with the vicissitudes of his central character’s marriage across the years. Yet Palliser (later Duke of Omnium, no less) is often peripheral to Trollope’s socio-political interests. The sense of a protagonist who is a means to an end is even stronger in the great English roman fleuve of the mid-20th century, Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time. Powell’s narrator, Nicholas Jenkins, is so much like a lens through which we view the unravelling follies of his acquaintances that we often hardly notice him. He loves and works and suffers in the margins of his own narrative.

No one could say this about Adrian Mole, as living a character as comic fiction has known. By the last instalment of his diary, the comedy has darkened a little, naturally. The adolescent Adrian may have declared Crime and Punishment is “the most true book I have ever read”, but you get to the end of the first volume of his diaries, and just into the 15th year of his life, without any tragic events. Seven books and 25 years later there have been deaths, divorces and real disasters. But hope, as well as disappointment, springs eternal. A lesson in rueful pertinacity, his parents Pauline and George are alive and opinionated still, and – after all their separations – back together and living next door to their appalled son. When we hear the middle-aged Adrian we remember the younger Adrian. He is only so frequently disappointed because he hopes for better. On that original birthday he hoped that he was growing into a better self. “So at last I am fourteen. Had a good look at myself in the mirror tonight and think I can detect a certain maturity”. Whether 14 or 40 or later still, we surely recognise, Adrian Mole, c’est moi.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion