Abstract

Background

Although Asian Americans are at high risk for type 2 diabetes, it is not known whether they are appropriately screened for this disease.

Objective

To assess racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes screening between Asian Americans and other adults.

Design

Analysis of pooled cross-sectional data from 45 U.S. states and territories using the 2012–2014 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. We calculated the weighted proportions of adults in each racial and ethnic group who received recommended diabetes screening. To assess for racial and ethnic disparities, we used multivariable logistic regression to model receipt of recommended diabetes screening as a function of race and ethnicity, adjusting for demographics, healthcare access, survey year, and state.

Participants

A total of 526,000 adults who were eligible to receive diabetes screening according to American Diabetes Association guidelines from 2012 to 2014 (age ≥ 45 years or age < 45 years with a body mass index [BMI] ≥ 25 kg/m2).

Main Measures

Self-reported receipt of diabetes screening (defined as a test for high blood sugar or diabetes within the past 3 years) and self-reported race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic Asian, non-Hispanic Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaskan Native, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic or Latino, and non-Hispanic multiracial or other).

Key Results

Asian Americans were the least likely racial and ethnic group to receive recommended diabetes screening. Overall, Asian Americans had 34% lower adjusted odds of receiving recommended diabetes screening compared to non-Hispanic whites (95 % CI: 0.60, 0.73). In subgroup analyses by age and weight status, disparities were widest among obese Asian Americans ≥ 45 years (AOR = 0.56; 95 % CI: 0.39, 0.81). Disparities persisted among Asian Americans who completed other types of preventive cancer screening.

Conclusions

Despite their high risk of diabetes, Asian Americans were the least likely racial and ethnic group to receive recommended diabetes screening.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Pervasive racial and ethnic health disparities have been documented throughout the U.S. population.1 , 2 An increasing number of studies have focused specifically on disparities among Asian Americans,3 , 4 the most rapidly growing racial and ethnic population in the United States.5 One particularly critical disparity for this population is their elevated risk of type 2 diabetes.5 – 8 Diabetes prevalence is approximately 21 % among Asian Americans, nearly twice as high as in non-Hispanic whites.8 Notably, Asian Americans have a lower mean body mass index (BMI) than other racial and ethnic groups, but are more likely to develop type 2 diabetes.8 – 11 The high risk of diabetes among Asian Americans has been attributed to a combination of genetic,6 physiologic,6 , 12 , 13 and environmental factors.14 – 16

Given the growing public health attention on the elevated risk of type 2 diabetes among Asian Americans, the expectation is that clinicians would intensify efforts to appropriately screen this population. However, a previous study demonstrated that the rate of undiagnosed diabetes among Asian Americans was almost three times as high as that in non-Hispanic whites.8 This finding suggests that many Asian Americans may not receive appropriate diabetes screening. To date, no research has explicitly investigated this possibility.

We used 2012–2014 data from a large national survey to examine whether Asian Americans are appropriately screened for type 2 diabetes and to assess racial and ethnic disparities in recommended diabetes screening between Asian Americans and other adults. We also performed several analyses to investigate whether patient- or system-level factors may be potential mediators of disparities in diabetes screening.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

We analyzed pooled cross-sectional data from the 2012–2014 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), an annual nationally representative telephone-based survey that collects information on the health-related risk behaviors and preventive health practices of U.S. residents.17 The survey is conducted in English or Spanish only. The BRFSS includes a core module and optional modules that are implemented on a state-by-state basis. We limited our sample to 42 states and three U.S. territories that implemented the optional Pre-Diabetes module at least once between 2012 and 2014, since this module contained information on our study’s dependent variable (Online Appendix Table 1). We excluded eight states that did not implement this module: California, Colorado, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Texas, and Utah.

Study Variables

The dependent variable in our analysis was self-reported receipt of diabetes screening (“Have you had a test for high blood sugar or diabetes within the past 3 years?”). The primary independent variable was self-reported race and ethnicity, which was categorized in the BRFSS as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic Asian American, non-Hispanic Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaskan Native, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic or Latino, non-Hispanic multiracial, or non-Hispanic other. For this analysis, we combined non-Hispanic multiracial and non-Hispanic other adults into one group, because national diabetes screening guidelines do not specify recommendations for either of these groups.18 – 20

Study Population

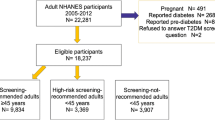

Our study population included adults who should be screened for type 2 diabetes based on the American Diabetes Association (ADA) guidelines between 2012 and 2014. During each of these years, the ADA guidelines recommended diabetes screening with a fasting blood sugar, hemoglobin A1c, or oral glucose tolerance test every 3 years for all adults aged ≥ 45 years and all adults aged < 45 years with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 who had at least one additional risk factor for diabetes.18 – 20 We considered all adults aged < 45 years with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 to be eligible for diabetes screening, since previous research suggests that the vast majority of overweight and obese adults have at least one additional risk factor that qualifies them for diabetes screening under the ADA guidelines (e.g., racial/ethnic minority status, sedentary lifestyle, family history, etc.).21 Please see the Online Appendix and Appendix Table 2 for further details. We excluded adults who reported having diabetes or pre-diabetes, since adults with these conditions are managed differently from the general population under ADA guidelines (i.e., more frequent testing).20

Among the 565,530 adults who met initial sample inclusion criteria, we excluded 25,215 respondents (4.5 %) who reported that they did not know (DK), were not sure (NS), or refused to give an answer (R) to the diabetes screening question. Of these excluded respondents, 274 were Asian American. We additionally excluded 9170 respondents (1.6 %) who reported DK/NS/R to the race/ethnicity question, as well as 5145 respondents (0.9 %) who reported DK/NS/R for key covariates (education category, routine check-up in the past 2 years, enrollment in a health insurance plan, and having a usual source of care22). Our final sample consisted of 526,000 respondents who were eligible for diabetes screening, including 9310 Asian Americans.

Statistical Analysis

We used survey-weighted descriptive statistics to characterize the demographic characteristics and healthcare access of our sample, as well as to calculate the weighted proportion of adults in each racial and ethnic group who received recommended diabetes screening. We defined disparities as the adjusted difference in recommended diabetes screening between Asian Americans and other adults, assuming that the distribution of important covariates between groups was similar (referred to as the “residual direct effect” approach).23 To implement this definition, we fit multivariable logistic regression models to assess receipt of diabetes screening as a function of race and ethnicity (using non-Hispanic white as the referent group), controlling for demographic variables (continuous age, gender, education category, residence in a metropolitan area), dichotomous healthcare access variables (routine check-up in the past 2 years, enrollment in a health insurance plan, having a usual source of care), survey year indicators, and state indicators. We excluded annual household income from our main model specifications because 13.9 % of our sample had missing data for this variable, similar to prior studies using the BRFSS.24 , 25 In sensitivity analyses, we found that results did not change substantially when we excluded individuals with missing income data and adjusted for income, or when we adjusted for imputed income in regression models (Online Appendix Table 3).

To further characterize patterns of racial and ethnic disparities in screening, we conducted subgroup analyses examining whether the magnitude of disparities varied by age group (age < 45 or age ≥ 45) and/or BMI category (normal weight or underweight: BMI < 25 kg/m2; overweight: BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2; obese: BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). We also conducted analyses to investigate potential mechanisms that might explain disparities in diabetes screening. To determine the role of demographic characteristics and healthcare access, we removed each covariate individually from regression models and assessed for changes in the magnitude of the disparity. Though we could not directly examine the role of patient preference and attitudes toward healthcare, we conducted three analyses that indirectly examined these factors. First, we assessed racial and ethnic disparities in the receipt of other forms of preventive screening, reasoning that similar disparities could suggest a general aversion to screening among Asian Americans. Specifically, we assessed racial and ethnic disparities in the receipt of lifetime breast cancer screening among women aged ≥ 50 years and colorectal cancer screening among all adults aged ≥ 50 years. We used age ≥ 50 years as the cutoff for breast cancer screening for consistency across the two analyses, and because there is consensus among national guidelines that all women above this age should receive breast cancer screening.26 , 27 Unlike our main analysis, this analysis assessed all Asian Americans aged ≥ 50 years in the 2012–2014 BRFSS and did not exclude individuals with diabetes or pre-diabetes, because we were interested in comparing preventive cancer screening rates to diabetes screening rates.

Second, we assessed racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes screening among 1) adults aged ≥ 50 years who had ever received colorectal cancer screening; 2) women aged ≥ 50 years who had ever received breast cancer screening; and 3) women aged ≥ 50 who had ever received both colorectal cancer and breast cancer screening. Since these screening tests are logistically and technically more involved than diabetes screening, we reasoned that individuals who completed these tests would be unlikely to decline a minimally involved test such as diabetes screening.

Finally, to examine the possibility that disparities in screening may be driven by higher dissatisfaction or distrust of the healthcare system, we assessed whether the magnitude of disparities changed substantially when we additionally controlled for patient satisfaction in regression models (“In general, how satisfied are you with the healthcare you received?”).28 Of note, data on the patient satisfaction item were included in an optional healthcare access module beginning in 2013. Thus, this analysis included only the 277,844 respondents in our sample who were asked this question in the 2013 and 2014 BRFSS.

In all analyses, we employed survey weights and design-based variance estimators to account for the complex survey design of the BRFSS. Data analysis was conducted using STATA, version 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). This study was exempted from review by the institutional review board of the University of Chicago.

RESULTS

Our sample of 526,000 respondents represented 229.7 million U.S. adults who were eligible for diabetes screening between 2012 and 2014, of whom 71.3 % were non-Hispanic whites and 2.2 % were Asian Americans. Compared to non-Hispanic whites, Asian Americans in our sample were younger, more highly educated, more likely to be overweight, and less likely to be obese (Table 1).

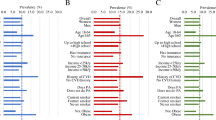

The weighted percentage of Asian American adults receiving recommended diabetes screening was 47.1 %, which was lower than the percentage for non-Hispanic whites (59.2 %), non-Hispanic Pacific Islanders (50.3 %), non-Hispanic American Indians or Alaskan Natives (55.6 %), non-Hispanic blacks (60.2 %), Hispanics/Latinos (58.1 %), and adults classified as multiracial or other (58.8 %) (Table 2).

Compared to non-Hispanic whites, the adjusted odds of receiving recommended diabetes screening were significantly lower among Asian Americans in the overall sample (AOR = 0.66; 95 % CI: 0.60, 0.73; Table 2), in the subgroup of adults aged ≥ 45 years (AOR = 0.58; 95 % CI: 0.51, 0.66), and in the subgroup of adults aged < 45 years with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (AOR = 0.78; 95 % CI: 0.67, 0.90). In contrast, the adjusted odds of receiving recommended diabetes screening were significantly higher among non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics/Latinos compared to non-Hispanic whites in all analyses (Table 2). Results did not change substantially when we removed each covariate individually from regression models to assess for changes in the magnitude of the disparity (Online Appendix Table 4).

We also assessed racial and ethnic disparities among subgroups defined by age and BMI category. Compared to non-Hispanic whites, Asian Americans aged ≥ 45 years who were underweight/normal weight, overweight, or obese were all significantly less likely to receive recommended diabetes screening; the magnitude of this disparity was greatest for obese adults (AOR = 0.56; 95 % CI: 0.39, 0.81; Table 3). Compared to non-Hispanic whites, obese Asian Americans aged < 45 years were significantly less likely to receive recommended diabetes screening (AOR = 0.74; 95 % CI: 0.54, 0.999), but differences were not statistically significant for overweight adults aged < 45 years (Table 3).

Compared to non-Hispanic whites, Asian Americans were significantly less likely to report receiving colorectal cancer screening (AOR = 0.60; 95 % CI: 0.53, 0.68), but this was not true for breast cancer screening (Online Appendix Table 5). Compared to non-Hispanic whites, the adjusted odds of receiving recommended diabetes screening remained significantly lower among Asian Americans aged ≥ 50 years who had ever received colorectal cancer screening (AOR = 0.59; 95 % CI: 0.47, 0.76), for Asian American women aged ≥ 50 years who had ever received breast cancer screening (AOR = 0.62; 95 % CI, 0.45, 0.84), and for Asian American women aged ≥ 50 years who had ever received both colorectal and breast cancer screening (AOR = 0.60; 95 % CI: 0.41, 0.88; Table 4). Among individuals with patient satisfaction data, additionally controlling for patient satisfaction did not substantially change the magnitude of the disparity (Online Appendix Table 6).

DISCUSSION

We found that less than half of Asian Americans received recommended type 2 diabetes screening between 2012 and 2014. While screening was suboptimal in all racial and ethnic groups, Asian Americans were by far the least likely group to be appropriately screened. In regression models adjusting for important demographic and healthcare access variables, Asian Americans had 34 % lower odds of receiving recommended diabetes screening compared to non-Hispanic whites. Our findings suggest that inadequate screening among Asian Americans may be an important driver of the high prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes in this population.8

Our study provides evidence against several potential explanations for the disparity in diabetes screening between Asian Americans and other adults. First, the disparity is unlikely driven by differences in clinical need, since our sample included only individuals who should receive diabetes screening according to ADA guidelines. Second, the disparity is unlikely driven by differences in healthcare access or patient demographic factors (e.g., gender, insurance status), since estimates of the disparity did not change substantially when we removed these variables individually from regression analyses.

Our study does not provide strong support for the hypothesis that differences in patient preference and attitudes toward healthcare are the primary mediators of the observed disparity. For example, while Asian Americans in our study reported receiving less recommended colorectal cancer screening;26 , 29 this was not true for breast cancer screening. Additionally, we also found that disparities in diabetes screening persisted among Asian Americans who completed recommended breast and/or colorectal cancer screening, both of which are logistically and technically more involved than diabetes screening. This finding suggests that at least in this group of older adults, the disparity is not likely to be driven by patient attitudes toward screening. Finally, results did not change substantially when we additionally controlled for patient satisfaction, which has been associated with higher adherence to physician recommendations in prior studies.28

At least two additional possibilities remain. One possibility is that Asian American patients may not recognize their elevated risk for diabetes, and thus they request diabetes screening less frequently than other racial and ethnic groups. A second possibility is that clinicians may not adhere to evidence-based diabetes screening guidelines for Asian Americans,3 because clinicians also fail to recognize the elevated risk of diabetes in this population. Such a possibility would be consistent with previous work suggesting that the “model minority myth” and other stereotypes may impede clinician recognition of common health problems in Asian Americans (e.g., hypertension, dementia).30 – 32 Similarly, clinicians may be less likely to recognize or respond to obesity in Asian American patients compared to other adults. In potential support of this hypothesis, we found that among adults aged ≥ 45 years, the magnitude of the disparity in diabetes screening was unexpectedly widest for obese adults.

Our findings have important implications for clinical practice. In 2015, the ADA changed its guidelines to recommend screening in all Asian American adults aged < 45 years with a BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2 instead of 25 kg/m2.33 However, we demonstrate that disparities were also substantial among older Asian Americans, regardless of weight status. Thus, while the new ADA screening guidelines and related public health campaigns7 such as “Screen at 23” are important in promoting screening among younger Asian Americans, raising awareness about screening in older Asian Americans may be equally important.

We also note that the change in BMI cutoffs specified by the 2015 ADA guidelines also applied to Pacific Islanders, who are often grouped together with Asian Americans due to common biological and genetic factors.6 , 34 While our study focused on Asian Americans and may have been underpowered for analyzing Pacific Islanders, we do note that the magnitude of disparities was larger for Asian Americans than for Pacific Islanders. This finding suggests that Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders should not be combined in analyses of disparities, as doing so may mask important underlying differences.35

This study has several limitations. First, our dependent variable was based on self-reported information and was not subject to external validation. It is possible that some patients did not recall or were not aware that they had received diabetes screening, and as a result, we may have underestimated the proportion of adults who received diabetes screening. However, for this bias to explain the observed disparity, the magnitude of bias would have to be very large and would impact Asian Americans substantially more than other racial and ethnic groups. This is unlikely, since a prior study found that recall bias in BRFSS survey items was relatively uniform among racial and ethnic groups.36 Additionally, we analyzed a sample of Asian Americans with high rates of English fluency and controlled for education, a marker of health literacy that could potentially affect the recall or recognition diabetes screening.

Second, the Asian Americans in our sample had higher educational attainment and English fluency than the general Asian American population.5 , 37 Prior studies have shown that higher educational attainment and language fluency are associated with fewer barriers to healthcare and greater receipt of recommended healthcare.38 – 40 Thus, in a more representative sample of Asian Americans, with lower educational attainment and poor English fluency, the magnitude of the disparity could be even larger than we report.

Third, BRFSS data do not provide consistent information regarding Asian American subgroups (e.g., Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese) or immigration status. Asian Americans are a heterogeneous population, and more granular analyses between subgroups may reveal markedly different patterns in healthcare. Finally, while our study is representative of 45 U.S. states and territories, our sample did not include Texas or California, two states containing a large proportion of the U.S. Asian American population,5 including almost half of all Asian American immigrants.41 Inclusion of these states may have resulted in larger disparities in diabetes screening, due to lower English fluency among immigrants.39 Alternatively, it is possible that including these states may have resulted in smaller disparities, due to higher awareness of Asian American health issues.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study of 45 U.S. states and territories, we report that Asian Americans are not adequately screened for type 2 diabetes, and receive recommended screening less frequently than other racial and ethnic groups. Given the deleterious health effects of delayed diagnosis and treatment of diabetes, it is crucial that public health and clinical professionals improve screening and diagnosis of diabetes in Asian Americans.

References

Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: understanding racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 2002.

Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):e60–76.

Islam NS, Kwon SC, Wyatt LC, et al. Disparities in diabetes management in Asian Americans in New York City compared with other racial/ethnic minority groups. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(Suppl 3):S443–446.

Trinh-Shevrin C, Kwon SC, Park R, Nadkarni SK, Islam NS. Moving the dial to advance population health equity in New York City Asian American populations. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(Suppl 3):e16–25.

Hoeffel EM, Rastogi S, Kim MO, Shahid H. The Asian population: 2010. Washington, D.C: U.S. Census Bureau; 2012.

World Health Organization Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363(9403):157–163.

Hsu WC, Araneta MR, Kanaya AM, Chiang JL, Fujimoto W. BMI cut points to identify at-risk Asian Americans for type 2 diabetes screening. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(1):150–158.

Menke A, Casagrande S, Geiss L, Cowie CC. Prevalence of and trends in diabetes among adults in the United States, 1988-2012. JAMA : J Am Med Assoc. 2015;314(10):1021–1029.

McNeely MJ, Boyko EJ. Type 2 diabetes prevalence in Asian Americans: results of a national health survey. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(1):66–69.

Hsu WC, Boyko EJ, Fujimoto WY, et al. Pathophysiologic differences among Asians, native Hawaiians, and other Pacific Islanders and treatment implications. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(5):1189–1198.

King GL, McNeely MJ, Thorpe LE, et al. Understanding and addressing unique needs of diabetes in Asian Americans, native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(5):1181–1188.

Wang J, Thornton JC, Russell M, Burastero S, Heymsfield S, Pierson RN Jr. Asians have lower body mass index (BMI) but higher percent body fat than do whites: comparisons of anthropometric measurements. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;60(1):23–28.

Kadowaki T, Sekikawa A, Murata K, et al. Japanese men have larger areas of visceral adipose tissue than Caucasian men in the same levels of waist circumference in a population-based study. Int J Obes (2005). 2006;30(7):1163–1165.

Goel MS, McCarthy EP, Phillips RS, Wee CC. Obesity among US immigrant subgroups by duration of residence. JAMA : J Am Med Assoc. 2004;292(23):2860–2867.

Argeseanu Cunningham S, Ruben JD, Narayan KM. Health of foreign-born people in the United States: a review. Health Place. 2008;14(4):623–635.

Singh GK, Siahpush M, Hiatt RA, Timsina LR. Dramatic increases in obesity and overweight prevalence and body mass index among ethnic-immigrant and social class groups in the United States, 1976–2008. J Community Health. 2011;36(1):94–110.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey questionnaire. Atlanta, Georgia. 2012.

Professional Practice Committee of the American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes--2012. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(Suppl. 1):S11–S63.

Professional Practice Committee of the American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes--2013. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(Suppl. 1):S11–S66.

Professional Practice Committee of the American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes--2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(Suppl. 1):S14–S80.

Bullard KM, Ali MK, Imperatore G, et al. Receipt of glucose testing and performance of two US diabetes screening guidelines, 2007-2012. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0125249.

Blewett LA, Johnson PJ, Lee B, Scal PB. When a usual source of care and usual provider matter: adult prevention and screening services. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(9):1354–1360.

Cook BL, McGuire TG, Zaslavsky AM. Measuring racial/ethnic disparities in health care: methods and practical issues. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(3 Pt 2):1232–1254.

Ross JS, Bradley EH, Busch SH. Use of health care services by lower-income and higher-income uninsured adults. JAMA : J Am Med Assoc. 2006;295(17):2027–2036.

Kenney GM, Zuckerman S, Goin D, McMorrow S. Virtually every state experienced deteriorating access to care for adults over the past decade. Urban Institute, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; May 2012.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cancer screening—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(3):41–45.

Oeffinger KC, Fontham EH, Etzioni R, et al. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314(15).

Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD, Franks P. The cost of satisfaction: a national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(5):405–411.

Kandula NR, Wen M, Jacobs EA, Lauderdale DS. Low rates of colorectal, cervical, and breast cancer screening in Asian Americans compared with non-Hispanic whites: cultural influences or access to care? Cancer. 2006;107(1):184–192.

Weir RC, Tseng W, Yen IH, Caballero J. Primary health-care delivery gaps among medically underserved Asian American and Pacific Islander populations. Public Health Rep. 2009;124(6):831–840.

Tendulkar SA, Hamilton RC, Chu C, et al. Investigating the myth of the “model minority”: a participatory community health assessment of Chinese and Vietnamese adults. J Immigrant Minor Health. 2012;14(5):850–857.

Kim PY, Lee D. Internalized model minority myth, Asian values, and help-seeking attitudes among Asian American students. Cult Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2014;20(1):98–106.

Professional Practice Committee of the American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2015. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(Suppl. 1):S1–S2.

Chan JC, Malik V, Jia W, et al. Diabetes in Asia: epidemiology, risk factors, and pathophysiology. JAMA. 2009;301(20):2129–2140.

Bitton A, Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. Health risks, chronic diseases, and access to care among US Pacific Islanders. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(5):435–440.

Stein AD, Courval JM, Lederman RI, Shea S. Reproducibility of responses to telephone interviews: demographic predictors of discordance in risk factor status. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;141(11):1097–1105.

Gambino CP, Acosta YD, Grieco EM. English-speaking ability of the foreign-born population in the United States: 2012. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Commerce: Economics and Statistics Administration. 2014.

Winkleby MA, Jatulis DE, Frank E, Fortmann SP. Socioeconomic status and health: how education, income, and occupation contribute to risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(6):816–820.

Jacobs EA, Karavolos K, Rathouz PJ, Ferris TG, Powell LH. Limited English proficiency and breast and cervical cancer screening in a multiethnic population. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(8):1410–1416.

Cheng EM, Chen A, Cunningham W. Primary language and receipt of recommended health care among Hispanics in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl 2):283–288.

Gryn T, Gambino C. The foreign born from Asia: 2011. U.S. Census Bureau. 2012.

Acknowledgments

E. Tung was supported by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality training grant in health services research AHRQ T32HS000078. E. Tung, A. Baig, E. Huang, and N. Laiteerapong were supported by the Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research NIDDK P30DK092949. E. Huang was also supported by NIDDK K24DK105340. N. Laiteerapong was also supported by NIDDK K23DK097283. E. Tung had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Author Contributions

Respective author contributions are as follows. Study concept and design: all authors. Acquisition of data: E. Tung. Analysis and interpretation of data: E. Tung and K.P. Chua. Drafting of the manuscript: E. Tung and K.P. Chua. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Statistical analysis: E. Tung and K.P. Chua. Administrative, technical, or material support: K.P. Chua. Supervision: K.P. Chua. Final approval of the version to be published: all authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 524 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tung, E.L., Baig, A.A., Huang, E.S. et al. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Diabetes Screening Between Asian Americans and Other Adults: BRFSS 2012–2014. J GEN INTERN MED 32, 423–429 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3913-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3913-x