Liver transplant pioneer Thomas Starzl dies aged 90

- Published

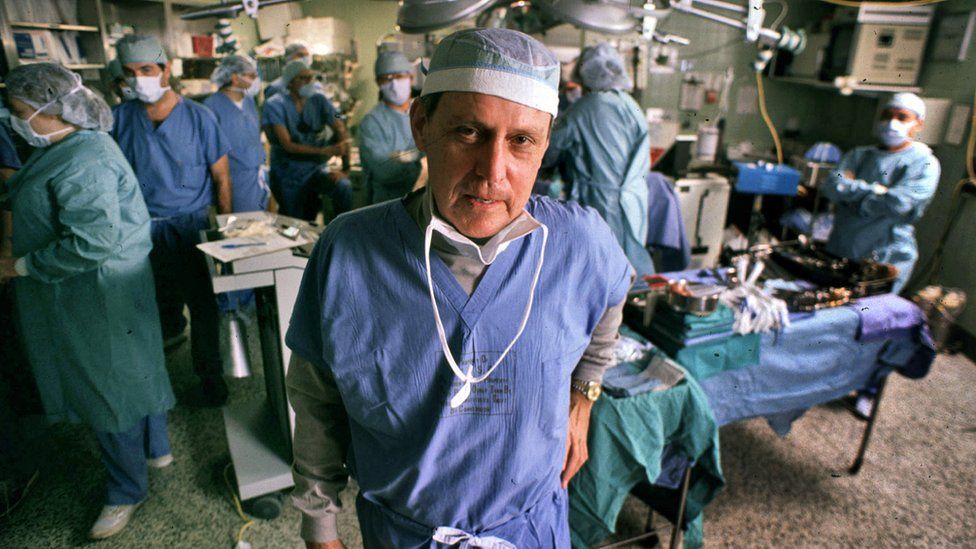

Dr Starzl, pictured in 1989, first carried out a procedure, which has since saved thousands of lives

Thomas Starzl, the man who performed the world's first liver transplant, has died days short of his 91st birthday.

The American surgeon pioneered the procedure in 1963, but his first patient did not survive.

After creating a new blend of anti-rejection drugs, he carried out the first successful transplant in 1967. Since then, thousands of lives have been saved by the procedure.

He died at home among his family, a spokesperson said.

In a statement, the University of Pittsburgh, which he joined in the 1980s to work on his drugs research, said Dr Starzl was known as the "father of transplantation" for his work in advancing the surgery from "from a risky, rare procedure to an accessible" one.

'A great human'

In addition to performing the first successful liver transplants, he experimented with transplants from cadavers, and refined the process by using identical twins and blood relatives.

He also pioneered animal-to-human liver transplants, including baboon to human experiments, which he showed could briefly extend life when there was a shortage of human organs.

His family issued a statement saying he "brought life and hope to countless patients".

"He was a pioneer, a legend, a great human, and a great humanitarian," it said.

"He was a force of nature that swept all those around him into his orbit, challenging those that surrounded him to strive to match his superhuman feats of focus, will and compassion."

Dr Starzl was also known for his research work on developing anti-rejection drugs. He blended azathioprine, a drug which suppresses the immune system, with steroids to aid in his pioneering transplants in the 1960s.

His research later in life would lead to the acceptance of improved drugs including cyclosporine and tacrolimus.

He retired from clinical work in 1991 and published his autobiography, The Puzzle People.

In it, he revealed that despite all his accolades, he felt a great anxiety about actually performing surgery.

"I had an intense fear of of failing the patients who had placed their health or life in my hands," he wrote.

"Even for simple operations I would review books.... then, sick with apprehension, I would go to the operating room, almost unable to function until the case began."

"Instead of blotting out the failures, I remembered these forever," he said.

- Published26 October 2016

- Published17 December 2016

- Published29 December 2016

- Published4 April 2014

- Published5 May 2013

- Published15 March 2013