The German groups of the late 1960s and 70s deliberately set out to create a form of music that owed nothing to Anglo-American rock’n’roll, and also wanted to make a decisive break from a past overshadowed by the second world war. As the drummer Jaki Liebezeit, who has died aged 78, said in the BBC Four documentary Krautrock: The Rebirth of Germany (2009): “The war was definitely finished. The old way of thinking had to be destroyed.”

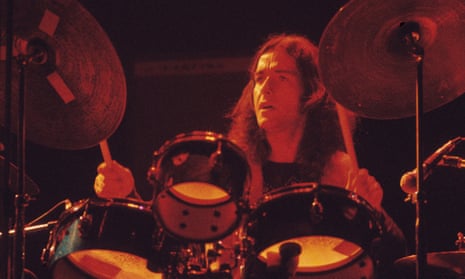

The so-called “motorik” beat, a minimalist, relentless form of rhythm practised by groups including Neu! and Kraftwerk, became one of the most distinctive trademarks of Germany’s postwar rock groups. Liebezeit, a founding member of the Cologne-based quintet Can, was also a skilled practitioner of the motorik approach, but he was much more besides.

He was able to incorporate a range of moods and styles into his playing, from African and funk rhythms to violent thrashing grooves, while always maintaining meticulous rhythmic control. His playing could veer from the heavy, pulverising beat he created on You Doo Right, from Can’s debut album Monster Movie (1969), to the lithe, off-kilter feel he brought to One More Night, from Ege Bamyasi (1972). On the title track of Flow Motion (1976), Liebezeit delivered a lesson in lean, bare-bones funkiness.

So precise and unswerving was Liebezeit’s playing, which included an ability to repeat drum patterns with uncanny precision, that he was likened to a human drum machine. To this he retorted that “the difference between a machine and me is that I can listen, I can hear and I can react to the other musicians, which a machine cannot do”. His particular gift was the ability to refine his drumming down to a compact, streamlined essence, so that when he did eventually add a fresh accent or extra beat it became a musical event of startling significance.

Born in Dresden, Liebezeit started out as a jazz drummer and played with a variety of artists including the jazz pianist Tete Montoliu and the trumpeter Chet Baker. In the mid-60s he joined the Manfred Schoof Quintet, fronted by the Magdeburg-born trumpeter who became a prominent figure in the development of European free jazz.

Can came together in 1968, their initial lineup comprising Holger Czukay (bass), Michael Karoli (guitar), Irmin Schmidt (keyboards) and the flautist and composer David C Johnson alongside Liebezeit. By the time Monster Movie was released, Johnson had been replaced by the vocalist Malcolm Mooney. The disc’s mix of psychedelia, avant-garde jazz, blues and experimental music was a preview of the avenues they would explore in the coming years.

Mooney soon returned to the US, suffering from mental health issues, and was replaced by Damo Suzuki, whom the group found busking in Munich. They brought him on stage to perform with them the same night, when, by strange chance, the Hollywood actor David Niven was in the audience. He was asked afterwards what he thought of the music. “It was great,” he said, “but I didn’t know it was music.”

Connoisseurs consider that Can reached their peak in their mid-70s albums, including Tago Mago (1971), Ege Bamyasi, Future Days (1973) and Soon Over Babaluma (1974), which leave an influential legacy, with their rich blend of ingredients from ambient and avant-garde sources to extended rock improvisations. The group signed to Virgin Records in 1975, after which their recordings assumed a more polished though slightly less stylistically inquisitive approach. In 1976 they scored a Top 30 single in the UK with the disco-influenced I Want More.

For their final 70s albums Saw Delight (1977), Out of Reach (1978) and Can (1979), the group were joined by two former members of the rock group Traffic, Rosko Gee and Rebop Kwaku Baah, while Czukay decided to quit the band in 1977. The group subsequently split, though there would be reunions in 1986 (which produced the album Rite Time, released three years later), then in 1991 and 1999.

Liebezeit went on to participate in several productive collaborations. In 1980 he formed Phantom Band, who made three albums, the most impressive of them being Freedom of Speech (1981). He also formed the ensembles Drums Off Chaos and Club Off Chaos, and collaborated with Czukay and the former Public Image Ltd bassist Jah Wobble on Czukay solo projects. In 1983 Liebezeit, Czukay, Wobble and The Edge from U2 recorded the mini LP Snake Charmer. Liebezeit played on Brian Eno’s album Before and After Science (1977) and on Depeche Mode’s Ultra (1997).

In the late 70s he played on a series of solo albums by Michael Rother, formerly of Neu! and Kraftwerk. In 2002 he formed a lasting partnership with the electronic producer/musician Burnt (or Bernd) Friedman, and their album Out in the Sticks (2005) featured a guest appearance by David Sylvian on vocals. The duo’s most recent recording was Secret Rhythms 5 in 2013.

Liebezeit had been scheduled to reunite with his former Can comrades Schmidt and Mooney for a concert at the Barbican Hall in London in April, billed as the Can Project.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion