Syntactic tunneling

« previous post | next post »

From Harry Asche:

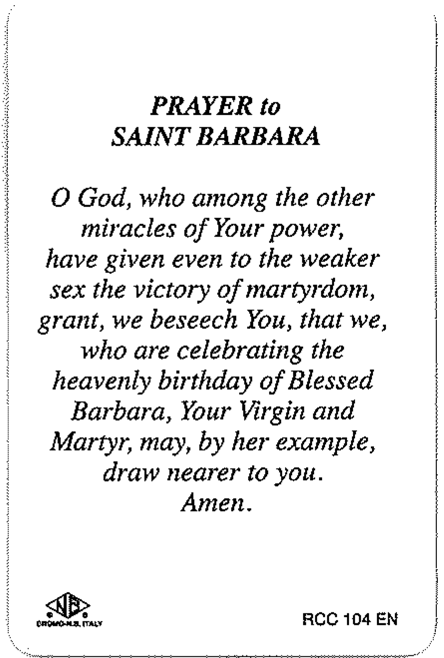

I am a tunnel engineer, and the patron saint of tunnelling is St Barbara. Her saint's day is the 4th of December. I am a bit of a tunnel nut, so on a visit to a church in Europe, I bought a St Barbara card, printed on a handy credit-card sized piece of plastic.

Here is the Prayer to St Barbara, transcribed exactly:

"O God, who among the other miracles of Your power, have given even to the weaker sex the victory of martyrdom, grant, we beseech You, that we, who are celebrating the heavenly birthday of Blessed Barbara, Your Virgin and Martyr, may, by her example, draw nearer to you. Amen."

I am greatly impressed by the complexity of the first sentence. The core is "O God grant that we may draw nearer to you." But this is interrupted by no less than six additional clauses. "That we" and "may" live in little islands on their own.

Is this a result of translation from the Latin? I did five years of Latin at school and it had a lasting negative affect on my ability to write English.

Harry's exposure to Latin is something that he shares with several hundred years of others writing in English and other European languages, and a few of them managed to become decent prose stylists.

But the waning of that influence is probably a large part of the reason for the secular decline in sentence length and syntactic complexity over the past couple of centuries. (See e.g. "The evolution of disornamentation", 2/11/2005; "Complexity", 9/7/2005; "Inaugural embedding", 9/9/2005; "Presidential parataxis?", 9/24/2009; "Real trends in word and sentence length", 10/31/2011.)

And the quoted prayer is certainly an extreme example of syntaxis rather than parataxis. Not all Latin-derived (or Greek-derived) prayers are so involuted — the vulgate Pater Noster and its familiar 1662 translation are syntactically straightforward. But the quoted prayer is certainly not the only example of its type.

I've never seen a theory about why (most) classical Latin (and Greek) writing was prone to syntaxis rather than parataxis, transcending the arguments about Attic vs. Asiatic style.

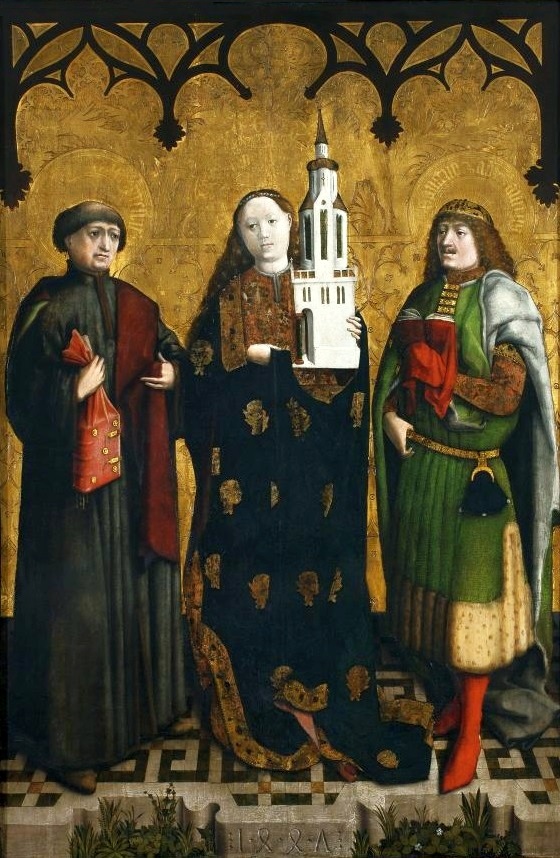

Anyhow, you can read about Saint Barbara here — she's "the patron saint of armourers, artillerymen, military engineers, miners, and others who work with explosives" — and here's an image of the prayer card:

Alan Jacobs said,

December 2, 2016 @ 7:08 am

The syntax in that prayer is a consequence of it taking the form of a "collect" (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collect), which typically has five parts, all of which are expected to go into one sentence — which they do, but often not without some pretty fancy subordinations. Here's another example, from the Anglican Book of Common Prayer:

"Almighty and everlasting God, who art always more ready to hear than we to pray, and art wont to give more than either we desire or deserve: Pour down upon us the abundance of thy mercy; forgiving us those things whereof our conscience is afraid, and giving us those good things which we are not worthy to ask, but through the merits and mediation of Jesus Christ, thy Son, our Lord. Amen."

The semicolon after "mercy" should probably be a comma, but given the difficulty of constructing and punctuating such a sentence, I'm inclined to be forgiving.

philip said,

December 2, 2016 @ 7:14 am

I will see your St Barbara and raise you an Archangel – just as complex, but here is the Latin too for comparison.

I think priests in general get worried that they are going to leave something out and so pile everything they can think of into the sentence.

Saint Michael the Archangel, defend us in battle, be our protection against the malice and snares of the devil. May God rebuke him we humbly pray; and do thou, O Prince of the Heavenly host, by the power of God, thrust into hell Satan and all evil spirits who wander through the world for the ruin of souls. Amen.

Sáncte Míchael Archángele, defénde nos in proélio, cóntra nequítiam et insídias diáboli ésto præsídium. Ímperet ílli Déus, súpplices deprecámur: tuque, prínceps milítiæ cæléstis, Sátanam aliósque spíritus malígnos, qui ad perditiónem animárum pervagántur in múndo, divína virtúte, in inférnum detrúde. Ámen

J.W. Brewer said,

December 2, 2016 @ 7:20 am

That sort of syntactic structure strikes me as entirely unexceptional for the specific genre in the specific register of liturgical/ecclesiastical English traditionally used for the genre. The genre in English largely started during the Reformation, with translations/adaptations of Latin texts, but I don't know how much of the syntaxis was due to a heavily literal translation of the Latin without modifying it to a more idiomatic-in-English style versus English prose style of 550 years ago itself being notably more pro-syntaxis than it is today, with more recent compositions in the specific genre sounding idiomatic-in-context if they followed the general structure of their Tudor-era predecessors.

This link has, if you scroll down, somewhat rough English versions of various Byzantine Greek prayers about or by (well, attributed to, although the actual historicity of the attributions may be uncertain …) St. Barbara. The medieval Greek literary tradition for such texts is notably different from the medieval Latin one, although it can be equally-or-more florid/turgid-sounding when rendered into English. http://full-of-grace-and-truth.blogspot.com/2011/12/st-barbara-great-martyr-of-heliopolis.html

Dan Curtin said,

December 2, 2016 @ 9:44 am

Alan is right. the Catholic (Latin) Breviary is full of collects with such constructions. Initially they are difficult for those with rusty (or debutant) Latin skills, but like the jokes at the back of Boys Life Magazine (1) the patterns quickly become routine.

(1) Showing my age, eh, Pedro?

Andrew (not the same one) said,

December 2, 2016 @ 10:15 am

It's interesting that this version of the collect, though in modernised English in some respects ('You' rather than 'Thou'), keeps the old syntax: a lot of modern translations use a more paratactic style, with 'O God, You have…' rather than 'O God, Who have…'. This may be in part because of uncertainty about whether it ought to be 'Who have' or 'Who has': the former is easier to justify grammatically, but sounds wrong to a lot of people. (Older translations, of course, had 'Who hast'.)

empty said,

December 2, 2016 @ 10:32 am

I remember only one joke from the back of Boy's Life:

Realtor: "Now this is a house without a flaw!"

Client: "Really? Why, what do you all stand on?"

J.W. Brewer said,

December 2, 2016 @ 11:30 am

To Andrew's point, I agree that the old "O God, who hast …" style sounds a bit odd when modernized, but the common alternative "O God, you have" seems problematic as well. Even if the syntax is less odd in general, it's very weird in the specific context because, dude, why the heck are you telling God stuff about Himself? He already knows. (Whereas by contrast the "O God, who hast" construction can more easily be understood as reminding the person saying the prayer or the congregation listening to the prayer about the particular detail of God's prior accomplishments, which, lacking omniscience, they could perhaps stand to be reminded of.)

Dan Lufkin said,

December 2, 2016 @ 11:37 am

To consider content rather than syntax for a moment, what's this stuff about giving "even to the weaker sex the victory of martyrdom"? Isn't this a kind of victory that a different religion is advocating nowadays? To the universal condemnation of St. Barbara's co-religionists?

Linda said,

December 2, 2016 @ 12:04 pm

@Dan Lufkin

It's the difference between being a murder victim and a suicide.

J.W. Brewer said,

December 2, 2016 @ 12:34 pm

One can simultaneously be opposed to the existence of persecution and also admire those who behave heroically under persecution, although it's probably true that a lot of these old prayers in praise of martyrs reflect a set of attitudes that were crystallized circa the fourth century (even if the specific text is a few centuries later than that) and are part of a worldview that requires some effort for moderns (well, moderns in parts of the world with no recent historical experience of rule by Communists or other persecutors of the Church) to make sense of.

Bill Benzon said,

December 2, 2016 @ 1:01 pm

"Attic vs. Asiatic style"

Contrast that with the argument in the opening chapter of Eric Auerbach's Mimesis, one of the most important works of 20th C literary criticism. Here's the Wikipedia description:

Pat Barrett said,

December 2, 2016 @ 2:10 pm

With trepidation I write: my Old Norse professor explained to us the difference between oral literature written down and stuff that starts out written. Written language can be more complex in sentence structure because it is easier to follow but requires substantial coordinating words, which are often borrowed from a prestige language like Greek (for Slavic), Persian (for Urdu), and Latin (for Western Europe), either directly or as calques. The question was: Is this a result of translation from the Latin? My reading tells me that participial constructions like the ablative absolute and "while watching" instead of "as they watched" would have seeped into English via deadly translation exercises from Latin to English, lending a Latinate tone to English sentence structure.

David Eddyshaw said,

December 2, 2016 @ 5:16 pm

The original Latin is:

Deus, qui inter caetera potentiae tuae miracula etiam in sexu fragili victoriam martyrii contulisti, concede propitius ut qui beatae Barbarae Virginis et martyris tuae natalitia colimus, per ejus ad te exempla gradiamur.

Richard Hershberger said,

December 2, 2016 @ 5:16 pm

My father was a career chaplain in the US Navy. One tour of duty he was the chaplain for a Marine artillery unit. This included presiding over the special service on the Feast of St. Barbara. This rather bemused him, a low(ish) church Lutheran, but military chaplains learn to go with the flow.

Chris C. said,

December 2, 2016 @ 8:21 pm

It strikes me as similar to a hymn sung at every Eastern Orthodox Divine Liturgy attributed to Emperor Justinian. The basic sentence is, "Only-begotten Son of God, save us!" but that's interrupted by about 6 or 7 expository clauses that really seem to be the point of the thing. One common translation runs,

David Marjanović said,

December 3, 2016 @ 1:30 pm

The Vatican itself no longer believes that St. Barbara ever existed. Venerating her, however, remains officially permitted in places where that's customary.

This part has a bit of the lack of syntax of Classical poetry: per eius exempla "by her examples" and ad te gradiamur "that we step closer to you" are strewn through each other.

J.W. Brewer said,

December 4, 2016 @ 12:02 pm

I managed to oversleep and miss Liturgy today, but fwiw the way I mentally parse the hymn Chris C. refers to is to take its syntactic core to be the comparatively simple structure "O Christ our God, trampling down death by death, save us." (The "save" needs to be stretched to two syllables to fit the chant melody.) All the stuff before that I treat as an increasingly complex accumulating sentence fragment that never quite gels into a complete sentence. It's as if one could punctuate it by sticking in an em-dash or ellipsis after all that stuff and just before "O Christ our God."

BZ said,

December 5, 2016 @ 3:41 pm

In at least the modern Jewish translations, things like "Our Father who Art in Heaven" have been modernized to "Our Father in Heaven" or even "Heavenly Father". It is much harder to give that kind of treatment to the example under discussion. In fact, attributions in second person singular feel strange because there is no need for them. You're already talking to the person in question, so there is no need to disambiguate, which is what such clauses usually do.