Fred Hellerman was the quiet Weaver, kind of the way George Harrison was the quiet Beatle.

He made his noise quietly.

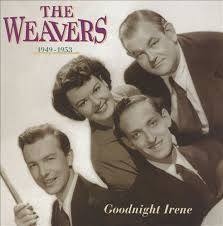

Hellerman, who died Thursday in Weston, Conn., at the age of 89, sang and played lead guitar in the Weavers, the fascinating, fractious and musically seminal folk music group of the early 1950s.

He was the last surviving original Weaver, preceded in death by Lee Hays in 1981, Pete Seeger in 2014 and Ronnie Gilbert last year.

They leave a legacy of striking contrasts.

The recordings that made them popular, like Leadbelly's Goodnight Irene, were heavily orchestrated to fit seamlessly with the pop tunes that dominated radio and jukeboxes in the era between the big bands and rock 'n' roll. There's nothing jarring about playing Goodnight Irene next to Dinah Shore's My Heart Cries For You.

Yet the Weavers's larger body of music was anything but comfortable pop. If On Top of Old Smokey was a campfire ballad, they were also singing Woody Guthrie songs about the people whose campfires were in hobo jungles. They sang union songs like Which Side Are You On and peace songs like Last Night I Had the Strangest Dream. Hays and Seeger wrote the powerful social justice anthem The Hammer Song, which became the pop hit If I Had a Hammer for Peter, Paul and Mary.

With Ronnie in a formal dress and the three guys in suits and ties, they became a popular television act, known for lovely harmonies and lively finger-popping tunes like Tzena, Tzena, Tzena.

At the same time, they were being tarred with the corrosive innuendo of the McCarthy era blacklist. When all four were accused of ties to communism, their bookings dried up and Decca cancelled their recording contract. By 1952 they had disbanded.

Like the others, Hellerman scrambled to cobble together a living. He wrote songs, he taught guitar. Then their manager Harold Leventhal took a crazy gamble and booked them into Carnegie Hall on Christmas Eve 1955.

It turned out actual people hadn't been scared off by the commie talk, and the success of that show gave the Weavers a second run that lasted more than eight years - though Seeger left in 1957 to go solo.

The Weavers got together one last time in 1980, to film a show for the documentary film Wasn't That a Time. It turned out to be a farewell for Hays, producing a loving and durable portrait of the group.

Hellerman acknowledged to Mary Katherine Aldin, who produced and wrote the liner notes for a four-CD 1993 Weavers box set, that Hays and Seeger were the two outsized personalities in the group. Seeger was hard to replace, he said, and Hays would have been impossible.

Hellerman also told Aldin he had loved playing with the Weavers and was "very grateful" for the movie.

That said, he admitted he had never fully sorted out the group's legacy.

It's easily and often said they were one of the most influential folk music ensembles of the 20th century, paving the path for what Dave Van Ronk called "the great folk scare" of the late 1950s and 1960s.

Hellerman said it was more nuanced than that.

"I suppose we did pave the way for Peter, Paul and Mary and the Kingston Trio and hundreds of others," Hellerman told Aldin, "many of which I wish we hadn't paved the way for."

Like who? Well, years earlier Hellerman told writer Robert Shelton that he didn't understand the accolades for Bob Dylan, who Hellerman felt had slim musical talent.

Hellerman also said he had "a lot of serious questions" about whether the Weavers, despite their best efforts, ever made a difference "in a larger way."

There was an undertone of frustration in that assessment, since he also told Aldin that concern about injustice was a primary reason he and Gilbert teamed up with Seeger and Hays in the late 1940s to form the Weavers in the first place.

"The immediate post-war period was a time of great social dislocation in this country," he told Aldin. "You had millions of servicemen coming back. Black soldiers coming back to Jim Crow after leaving Mississippi and going all over the world and finding that's not the way it had to be. Jobs, housing, price controls. That's partly what [the Hays/Seeger publication] People's Songs was about. We were all very much involved in that."

Accordingly, Hellerman said, the Weavers didn't start as a commercial enterprise. It started as four social activists, who happened to sing really well together, playing for fun and for people they thought would or should want to hear their message.

Around the time Irene was selling two million copies, the commercial element crept in. So did arguments. What should they sing, how should it sound, who should they sing it to. With four strong-willed and sometimes obstinate singers in one group, they argued a lot.

One of the reasons Seeger finally left in 1957, it was widely reported, was that the others wanted to make a cigarette commercial and Seeger considered cigarettes a vice they should not endorse just to make money.

Hellerman, the son of a Latvian immigrant, got his first exposure to music from the classical concerts his father listened to on the radio. Later, he told Aldin, he would skip school to go to the Paramount and hear big bands like Benny Goodman.

He taught himself to play guitar on a Coast Guard ship during the war, and after the Weavers he stayed active in music, most famously producing Arlo Guthrie's Alice's Restaurant.

His last public appearance was at Seeger's memorial service in 2014. If there is a next life, the Weavers can now resume singing and arguing there. The Quiet One is in the house.