UK centre to shoot for nuclear fusion record

- Published

The director of a UK science facility says scientists there will try to set a new world record in nuclear fusion.

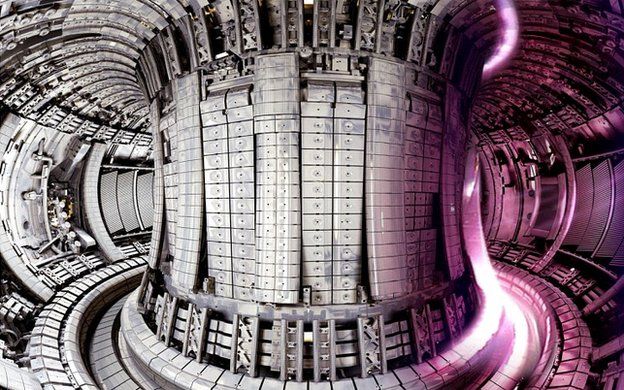

The Jet experiment in Oxfordshire was opened in 1984 to understand fusion - the process that powers the Sun.

Prof Steve Cowley told the BBC a go-ahead to run Jet at maximum power would allow scientists to try for the record by the end of the decade.

This could bring Jet up to the coveted goal of "breakeven" where fusion yields as much energy as it consumes.

Fusion is markedly different from current nuclear power, which operates through splitting atoms - fission - rather than squashing them together as occurs in fusion.

"We're hoping to repeat our world record shots and extend them," Prof Cowley, who is director of the Culham Centre for Fusion Energy - which hosts Jet, told BBC News.

"Our world record was from 1997, we think we can improve on it quite considerably and get some really spectacular results. We're winding up to that and by the end of the decade we'll be doing it."

Despite its history spanning some five decades, scientists hoping to harness fusion have faced many hurdles. But it remains an attractive prospect because it can yield a near limitless supply of clean energy.

The fusion community hopes their luck could change when the multi-bn-euro Iter fusion experiment comes online in Cadarache, in the south of France, in the 2020s. And officials from Jet, based at Culham, Oxfordshire, are now in the process of signing a contract that will keep the facility running for another five years.

Jet (Joint European Torus) was the prototype for Iter and over its extended lifetime will effectively carry out a dress rehearsal for that much bigger reactor, which will aim to demonstrate the scientific viability of fusion power at scale.

Prof Cowley also hopes to use the additional five years to train up young scientists who could eventually take their expertise to Iter.

During Jet's extended run, scientists will again begin using the deuterium-tritium fuel mix needed for maximum fusion power. Until recently, scientists had been running the experiment using deuterium fuel only. While running the experiment in this mode allows scientists to gather valuable scientific knowledge, both deuterium and tritium will be needed to exceed the record set by the Oxfordshire facility 17 years ago.

"Jet is the only machine in the world that can handle that fuel. When you put tritium in, it reacts like crazy," said Prof Cowley.

Jet uses the same approach to fusion as Iter. This is known as magnetic confinement fusion (MCF), in which electrically charged gas called plasma is heated to millions of degrees inside a sealed tube called a "tokamak".

The temperature inside Jet during one of its full power shots can soar to a scorching 200 million C. That's more than 10 times the temperature at the centre of the Sun - estimated to be about 15 million C.

In 1997, scientists pushed 24MW of energy into Jet and managed to get 16MW out - a fusion energy gain of about 0.7. A fusion energy gain factor (known as Q) of greater than one is required to achieve "breakeven", where the amount of energy produced equals the amount of energy consumed.

However, higher gain factors are required to achieve self-sustaining fusion, where the reactions continue without any external input of energy.

"We hope in the next runs of Jet that we'll approach a gain of one. But that's no good for energy production - you need a gain of 10, 20, 30 - much more energy coming than you put in. That's what Iter will do," said Prof Cowley.

Jet was the result of a European plan for fusion power conceived in the 1970s. Recently, the machine has undergone a series of upgrades to bring components in line with those planned for Iter. In coming years, it will shed light on some of the challenges for making fusion a success.

"The plasma is spewing out tank shells of neutron particles. The neutrons that come out of fusion are 10 times more energetic than those coming out of nuclear fission," said Steve Cowley.

"When they slam into the walls [of the tokamak] they rearrange the atoms in those walls. The question is can we have a material that doesn't mind having its atoms rearranged 10 times a year?"

In magnetic confinement experiments the plasma can become unstable, causing fusion to break down. However, improving performance is partly a matter of scale - and as Iter is likely to demonstrate - bigger really is better, as far as fusion is concerned.

In November 2013, the European Parliament formally endorsed the European Commission's 80bn-euro Horizon 20-20 research budget. This encompasses funds of about 300m euros to keep Jet running. Officials are currently finalising details of the settlement, with a view to signing the contract soon.

The National Ignition Facility in the US recently made a fusion breakthrough of its own. NIF takes a different approach to fusion from that taken by Jet and Iter, concentrating laser energy on a hydrogen fuel pellet to initiate fusion.

During a run of the experiment in September 2013, the small amount of energy released through the fusion reaction exceeded the amount of energy being absorbed by the fuel - a first at any fusion facility.

Follow Paul on Twitter.

Related Topics

- Published7 October 2013

- Published7 August 2013

- Published14 December 2011